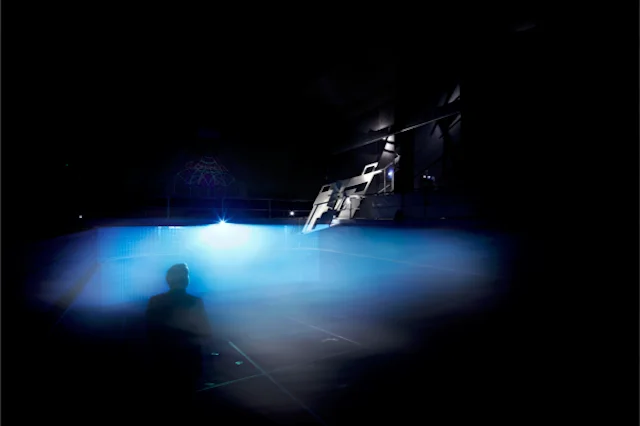

Image: Tanja Milbourne and Ben Milbourne, Just Like Swimming, 2013, Stattbad, Wedding, Germany. Fog, digital projection, variable dimensions. Courtesy the artists.

SECRETS & SURFACES

UrbanAU II: Just Like Swimming and The Secret Life of Buildings

June 2013, Stattbad, Wedding, Berlin

Artists / Architects:

ZAP, JUMBO, RusselL Isaac-Cole (Sydney)

Ben Milbourne, Tanja Milbourne (Melbourne)

Curators:

Claudia Perren, Miriam Mlecek (Sydney, Berlin)

Catalogue essay for Tanja Milbourne and Ben Milbourne.

In 1975, Gordon Matta-Clark demolished a massive conical hole through two 17th century townhouses in Paris. Sadly, he would not live to see the legacy of this intervention upon the site that would become the Centre Pompidou, an epicentre of controversial incursions into heritage by modernism.

Through his displacement of form through space, revealing the interior and exterior of the building in a disorienting whorl, Matta-Clark converted this unwanted architecture by subtracting from its once functional volume, erasing essential elements of the structural skin of the building, remaking it as a sculpture within and of space.

Fast-forward to present-day Berlin, where the once divided east and west are increasingly brought together through architectural development; where the spatial, historical and cultural differences of the past are being constantly merged and erased through functional reconstruction.

In the former inner west lies the Stattbad, designed in 1907 by Ludwig Hoffmann as a public swimming pool complex and more recently converted into a cultural centre. It is here that artists Ben Milbourne and Tanja Milbourne, working in architectural-photographic collaboration, created a series of interventions within one of the empty pools and across four further sites in the neighbouring suburbs.

In The Secret Life of Buildings, the artists' projections punched through the urban fabric of industrial and residential walls. Appearing as ex/implosions in the fabric of the façades, their light-based illusions revealed the imagined interiors of these buildings; empty spaces, lived spaces, abandoned spaces.

While the references in this work to Matta-Clark's interventions are clear, the methods differ; rather than physical deconstruction, the pair achieve the effects via photography and projection. Photography as a regular adjunct to architecture is most conspicuous, and often most passive, in its extension within the documentation process. Few developments, whether residential or commercial, could succeed without photographic documentation, representing the architectural form as object, enhancing its marketing and critical capacity with high resolution reproductions.

Here lies an important interest for the artists: how to reframe the relationship between architect and photographer from one of object-documentation, and move it toward a more collaborative relationship that reveals the interiority of both the representation and the site.

This type of photographic relationship can be seen in the reconstructions of Thomas Demand, James Casebere or in Filip Dujardin's series Fictions and Guimaraes; works that invert the functional relations of architecture, signifying the site as lived or 'real' space by questioning our perception of the reality of the photograph.

This interest can also be seen in the artist duo's earlier investigations Behind This Wall and 1:20 Room 1 (future archaeology), which exploited what lies behind the constructed surfaces of white-cubed gallery spaces in Melbourne and Berlin. In each of these series, Ben Milbourne and Tanja Milbourne combine their chosen fields to reveal the outside through the inside, bringing what may be hidden underneath to the surface.

If we consider architecture as site, as urban objects within a vast interconnected network of relational site-objects, how do we successfully inhabit them within the negotiation between private and public, commercial and domestic? When we are able to glance with x-ray vision into these spaces, as witnessed in The Secret Life of Buildings, we might question how these imagined projections alter our perceptions of how we live within this web of architecture: where the classical is subsumed by the modernist, where past and present jostle toward renovated entropy, where we are but temporary tenants in a vast ongoing event.

Presenting a spatial illusion of this kind also creates a momentary type of voyeurism into the sealed spaces of architecture, revealing this secret life within, the spaces we inhabit yet use to conceal our activities and interactions from the surrounding environment.

In this project, we can see photography working with rather than for architecture, operating as a three-dimensional medium with anamorphic projections, enabling both construction and light mediums to inhabit the same space, allowing the building to mediate itself, concealing and revealing the site as form, object, and lived space.

Continuing this spatial potential of the photographic-architectural form, the artists created a second work as part of their residency, pressing further into abstraction with more ephemeral and light-based media. Installed in one of the disused swimming pools at Stattbad, Just Like Swimming applied controlled light to construct another spatial illusion. Having filled the empty pool with fog generated by a smoke machine, the site was transformed from a once-was space through an elemental reference to its former function; most simply, a pool once filled with liquid and now an empty pool filled with gas.

In projecting blue light across the top of the pool and the upper limit of the fog, the work achieves a kind of illusory stasis, a shimmering surface, an illusion of refracting water. Engaging with the two spaces — the exterior of the pool and the interior container filled with vapourous substance — the viewer could literally step into the work and walk into the pool of light until submerged within the piece. To amplify the experience, the artists projected another layer within the pool: video imagery of swimmers from pools in and around Berlin, their bodies floating about, enhancing this submersion into illusion.

Being able to observe the installation from either outside the pool or submerged from within, the work triggers a memory of the built form, with the photographic and light mediums operating as a vehicle. How we perceive the reality of space, the 'real' space we inhabit, becomes split in Just Like Swimming, for we are submerged in a kind of light and atmosphere as we would be at any time of the day anywhere, yet here we are inside a concrete structure in a windowless building that performs a different function to its intended form. How does this displacement effect our perception of ourselves in space? What are we really seeing, what are we really building, where are 'we' in this constructed complexity?

This is a good place to leave you: floating in a pool of light with questions about space; but consider this quote from James Turrell, a master artist in light-based media, who most succinctly describes these kinds of complications between space and 'real' space:

'I literally made a whole new space out of the same physical space, which remained the same, although that’s not what you encountered perceptually. The example I like to give is the experience of sound when you are wearing good earphones or have a good stereo system. You find yourself in a music space that’s larger than the physical space you’re in. It’s the same when you’re reading: you become so engrossed in the book that you’re more in the space generated by the author than you are in the physical space where you are sitting. This extension to so-called “real” space is the space that we operate in all the time. Just look next to you at the stoplight and see that kid rocking back and forth with the music on. Is he in the same space you are? I don’t think so.'

Notes

From a series of conversation with the artists.

Elaine A. King, 'Into The Light: A Conversation with James Turrell' in Sculpture Magazine, Nov. 2002, Vol.21 No.9.